Using Graph Theory to Solve the Rubik’s Cube

Solving the Rubik's Cube using Graph Theory

Introduction

The Rubik’s Cube, with over 43 quintillion possible states, might seem unsolvable to many. But hidden beneath its colourful chaos is a deep structure rooted in graph theory.

The Cube as a Graph

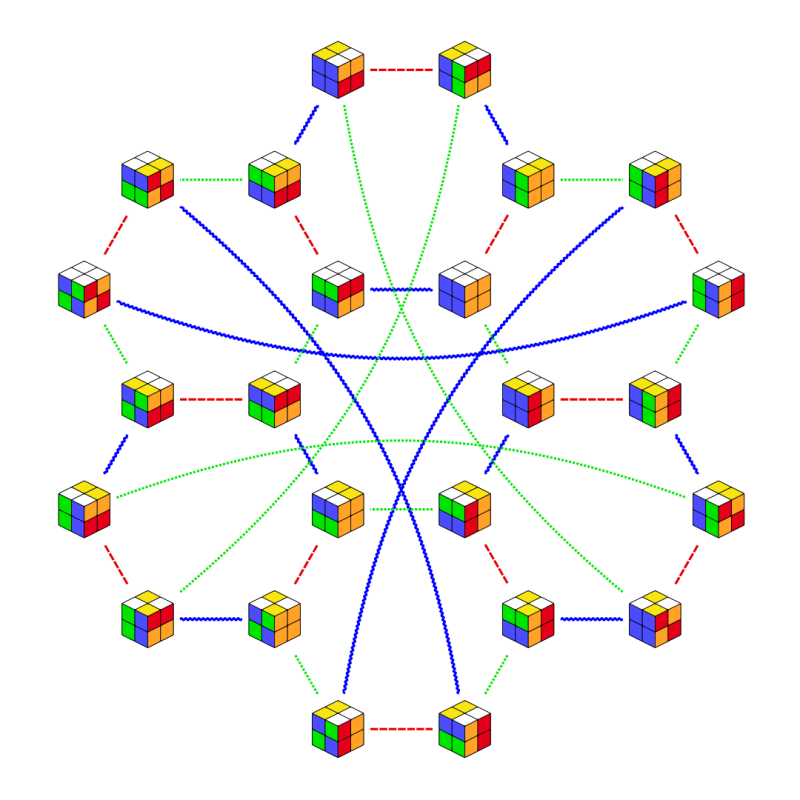

Imagine each state of the cube as a node in a graph. Each legal twist of the cube represents an edge connecting two nodes. This graph, often called the state-space graph, contains all the cube’s possible configurations and the moves connecting them.

Above: A simplified graph of cube states and transitions. The real graph has 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 nodes!

God's Number and Shortest Paths

Graph theory helps us answer a famous question:

What’s the minimum number of moves needed to solve any scrambled cube?

This is known as God’s Number. In 2010, it was proven that any state of the standard 3×3×3 Rubik’s Cube can be solved in 20 moves or fewer using the half-turn metric.

This discovery was made by treating the cube as a graph and running breadth-first search (BFS) and IDA* (Iterative Deepening A*) algorithms on massive computing clusters.

Search Algorithms in Practice

Graph-traversal algorithms play a huge role in cube-solving software.

Here are a few that work well:

- BFS – good for finding the shortest path (solution), but impractical for large depths.

- DFS – memory-efficient, but not optimal for shortest solutions.

A*andIDA*– best balance between speed and optimality. They use heuristics such as the number of misplaced facelets.

// Pseudocode for IDA* search on a cube graph

function IDAStar(start, goal) {

for (let threshold = heuristic(start); ; threshold++) {

const result = dfs(start, 0, threshold);

if (result.found) return result.path;

}

}

Overlapping-Circles Model of the 54 Facelets

Most graph-theory explanations treat each cube state as a node, but sometimes it helps to zoom in on the 54 individual stickers themselves.

The Idea

- Draw nine circles in the plane.

- Each circle hosts nine nodes, evenly spaced around its rim.

- Every node represents one facelet of the physical cube (54 total).

- Circles overlap, so a node that sits in two (or three) circles models how a single sticker is shared by adjacent layer turns.

Why nine circles?

The cube has three orthogonal axes (X, Y, Z). Along each axis you can rotate three parallel layers (left/centre/right, top/centre/bottom, front/centre/back). That gives 3 × 3 = 9 fundamental layer cycles. Each layer cycle is one of our circles.

Edges and Adjacency

Inside a circle: connect each node to its two neighbours, forming a 9-cycle.

Between circles: wherever two circles overlap, add an edge between the shared node copies. A quarter-turn of any layer is therefore just a permutation on the nodes of one circle, plus the necessary overlap edges.

(The full construction has 54 nodes, nine intra-circle 9-cycles, and many inter-circle edges—dense yet highly symmetric.)

Why This Matters

- Local heuristics – because every quarter-turn touches just one circle, search algorithms can restrict expansion to the relevant 9-cycle instead of the whole 54-node space.

- Edge-cut pruning – deleting an entire circle cleanly partitions the facelet graph into three subgraphs, giving tight heuristic bounds for

IDA*. - Symmetry detection – the drawing makes cube rotations obvious: rotate the diagram 90° and circles map to circles, nodes to nodes.

Symmetries and Group Theory

Graph theory overlaps with group theory in cube solving. The cube’s graph has many symmetries, reducing the number of unique positions we have to explore. Exploiting these symmetries is crucial for pruning the search space and speeding up algorithms.

Real-Life Applications

Techniques refined while solving the Rubik’s Cube influence:

- Robot pathfinding

- Automated planning

- Cryptography

- Molecular folding

Solving the cube isn’t just a party trick — it’s a showcase of elegant mathematical problem-solving.